I posted earlier this month about the

Grünfeld Defence, but given it's high popularity in Google searches that are used to discover the

Chess Tales blog, I'm happy to write more.

In this post, I'll tell you about a Grünfeld line we prepared for the European Chess Championships; Sophie didn't get the opportunity to use it, but I've played it twice myself recently with success. I'll also point you to the literature that's available and show you a couple of sample games.

The Grünfeld has featured in the repertoires of World Champions: Kasparov, Fischer, Botvinnik and Smyslov. The great Viktor Korchnoi used it regularly. In the early 50's he copied out and analysed a hundred Grünfelds as part of his preparation for the final of the 20th USSR Championships. Reportedly, when Alekhine was first confronted with the defence he resigned the game by hurling his king across the room.

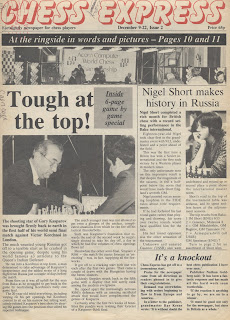

The Exchange variation (1 d4 Nf6; 2 c4 g6; 3 Nc3 d5; 4 cd Nxd5; 5 e4 Nxc3; 6 bc) is far and away the most common continuation, but amongst the 'sidelines', the Russian system (1 d4 Nf6; 2 c4 g6; 3 Nc3 d5; 4 Nf3 Bg7; 5 Qb3) remains interesting, leads to complex positions and has featured in high level encounters between Karpov and Kasparov, and famously between Botvinnik and Fischer at Varna in 1962 (see

My 60 Memorable Games(Amazon)

).

Earliest games in the opening (1922) were in the Exchange variation and went 6 ... Bg7; 7 Nf3. Eventually, White players started preferring a setup with 7 Bc4 and 8 Ne2, which gave rise to some interesting games where White sacrificed the exchange (rook on a1 for bishop on g7) and attacked the Black king, or got in an early Bxf7+ (which was played by Karpov in his Seville World Championship match with Kasparov). In the 80's though, there was a return to favour of 7 Nf3 (particularly in conjunction with 8 Rb1) and this became known as the Modern Exchange Variation.

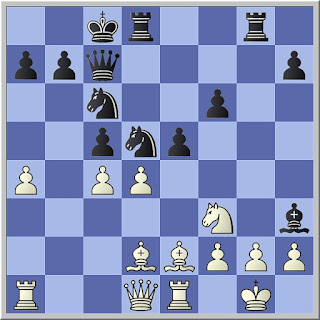

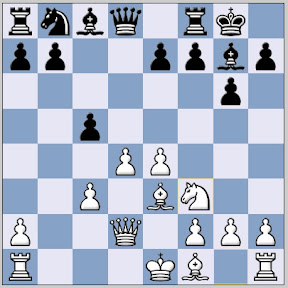

The variation we prepared for the European Chess Championships is a refinement on the Modern Exchange Variation: Instead of 7 Nf3, White first plays Be3 and then Qd2 before finally developing the Knight to f3. It was adopted by Karpov in his 1990 match with Kasparov, and has sound strategic foundations. After the usual continuation 7 Be3 0-0; 8 Qd2 c5; 9 Nf3 we reach the following position:

By playing the moves in this order, White avoids a ... Bg4 pin by Black which serves two motives: firstly it reduces the pressure that Black can apply on White's centre, and secondly White can avoid any Bg4xf3 simplifications and aim to cramp Black's position. We'll see a radical illustration of this in one of our sample games, after the continuation 9 ... Bg4; 10 Ng5!?.

Depending how Black plays, White now has some clear ideas in this position. 9 ... Nc6 is met by 10 d5 establishing a very strong central pawn phalanx, and 9 ... Qa5; 10 Rc1 e6 (preparing Nc6) can be met directly by 11 Bh6! looking to exploit the holes on the dark squares. Finally, White can meet 9 ... Qa5; 10 Rc1 cd; 11 cd Qxd2 with 12 Nxd2 and hope for a better ending.

This approach is explored in depth in

Beating the Indian Defences by Burgess and Pedersen. For those looking to play the Black side, I recommend taking a look at Rowson's

Understanding the Grünfeld or The

Grünfeld Defence by Nigel Davies. If you are looking a clear and simple guide to the concepts and variations there is Aagard's

Starting out: The Grünfeld. For an incredibly detailed investigation of some key games, you can also try Karpov's

Beating the Grunfeld (Amazon).

If you are looking to buy these books in the US you can try my Chess Online store.Here's Karpov avoiding the Bishop exchange against Kasparov:

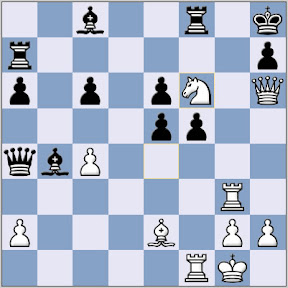

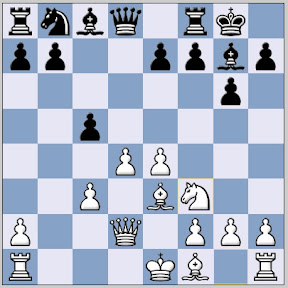

Anatoly Karpov - Garry Kasparov, 17th Game, World Championship, Lyon 19901.d4 Nf6 2.c4 g6 3.Nc3 d5 4.cxd5 Nxd5 5.e4 Nxc3 6.bxc3 Bg7 7.Be3 c5 8.Qd2 O-O 9.Nf3 Bg4 10.Ng5

This was Karpov's new move; this game is covered in depth in his "Beating the Grünfeld". I was delighted when I got the

opportunity to play it at Edinburgh last weekend, but couldn't convert an ending a pawn up.

cxd4 11.cxd4 Nc6 12.h3 Bd7 13.Rb1 Rc8 14.Nf3 Na5 15.Bd3 Be6 16.O-O Bc4 17.Rfd1 b5 18.Bg5 a6 19.Rbc1 Bxd3 20.Rxc8 Qxc8 21.Qxd3 Re8 22.Rc1 Qb7 23.d5 Nc4 24.Nd2 Nxd2 25.Bxd2 Rc8 26.Rc6 Be5 27.Bc3 Bb8 28.Qd4 f6 29.Ba5 Bd6 30.Qc3 Re8 31.a3 Kg7 32.g3 Be5 33.Qc5 h5 34.Bc7 Ba1 35.Bf4 Qd7 36.Rc7 Qd8 37.d6 g5 38.d7 Rf8 39.Bd2 Be5 40.Rb7 1-0

(I seem to be publishing a lot of Kasparov's losses on Chess Tales; he won quite a few games as well! I'll try to correct things in the coming weeks)And, here's Fischer's epic encounter with Botvinnik in the Russian System:

Mikhail Botvinnik - Bobby Fischer, Varna Olympiad 19621. c4 g6 2. d4 Nf6 3. Nc3 d5 4. Nf3 Bg7 5. Qb3 dxc4 6. Qxc4 O-O 7. e4 Bg4 8. Be3 Nfd7 9. Be2 Nc6 10. Rd1 Nb6 11. Qc5 Qd6 12. h3 Bxf3 13. gxf3 Rfd8 14. d5 Ne5 15. Nb5 Qf6 16. f4 Ned7 17. e5 Qxf4 18. Bxf4 Nxc5 19. Nxc7 Rac8 20. d6 exd6 21. exd6 Bxb2 22. O-O Nbd7 23. Rd5 b6 24. Bf3 Ne6 25. Nxe6 fxe6 26. Rd3 Nc5 27. Re3 e5 28. Bxe5 Bxe5 29. Rxe5 Rxd6 30. Re7 Rd7 31. Rxd7 Nxd7 32. Bg4 Rc7 33. Re1 Kf7 34. Kg2 Nc5 35. Re3 Re7 36. Rf3+ Kg7 37. Rc3 Re4 38. Bd1 Rd4 39. Bc2 Kf6 40. Kf3 Kg5 41. Kg3 Ne4+ 42. Bxe4 Rxe4 43. Ra3 Re7 44. Rf3 Rc7 45. a4 Rc5 46. Rf7 Ra5 47. Rxh7 Rxa4 48. h4+ Kf5 49. Rf7+ Ke5 50. Rg7 Ra1 51. Kf3 b5 52. h5 Ra3+ 53. Kg2 gxh5 54. Rg5+ Kd6 55. Rxb5 h4 56. f4 Kc6 57. Rb8 h3+ 58. Kh2 a5 59. f5 Kc7 60. Rb5 Kd6 61. f6 Ke6 62. Rb6+ Kf7 63. Ra6 Kg6 64. Rc6 a4 65. Ra6 Kf7 66. Rc6 Rd3 67. Ra6 a3 68. Kg1 1/2-1/2

If you want to know more about how I analyse Google (and other search engine) queries, see maps of the Chess Tales readers, and the mechanics of operating the blog, please let me know (either by comment or email to roger AT 21thoughts DOT com)and I'll give you the 'low-down'.